Editor’s Note: Today’s guest feature is submitted by Greg Moats, industry insider.

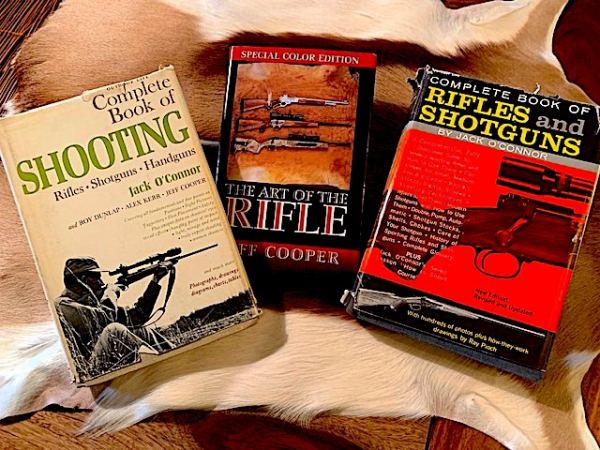

Two old and tattered books that changed my life along with a newer book that has recently influenced me greatly.

In 1965 I was 13, in the eighth grade and had a blossoming interest in firearms. My father was not what you’d call a “gun-guy” but neither was he negative, he just wasn’t interested in them. But he was interested in me and as a birthday present gifted me with a subscription to “Outdoor Life” and a membership in their book club. My first book order was comprised of two books that were destined to change my life: “The Complete Book of Shooting,” and “The Complete Book of Rifles and Shotguns.” 54 years later, their pages are yellowed, dog eared, highlighted and underlined; if I’ve ever gotten my money’s worth of anything, it certainly has been those two books. The life changing aspect is that they introduced me to Jack O’Connor and Jeff Cooper. O’Connor imbued in me a deep affinity for pre-64 Model 70 and Model 21 Winchesters and Cooper set me on the road to the mindset of “Practical Shooting.” They were both wonderful wordsmiths with very different styles and their areas of journalistic expertise didn’t overlap and therefore never conflicted. O’Connor was the champion of the .270, Cooper the High Priest of the .45 ACP.

For almost 20 years all was downhill and shady in my little gun world until Cooper introduced the concept of the Scout Rifle. In the O’Connor-hued part of my brain, the perfect all around rifle was a Pre-64 Model 70, wood stocked, Leupold-scoped rifle, preferably in .270 or .30/06. Cooper was now advocating a 19” barreled .308 with a low powered scope stuck way out on the barrel where I had only seen pictures of snipers from the Wehrmacht mount them. Not being a particularly active rifle shooter, it fortunately didn’t require any shifting of allegiance nor change of behavior so I did what any respectable hero-worshiper would do when their icons conflicted……I ignored it.

An early O’Connor influence had caused the author to believe that the Pre-64 Model 70 was the perfect rifle until he attended the Gunsite Scout Rifle course.

In 2002 when Cooper’s “The Art of the Rifle” was published, I purchased the first copy I could find. The section on the Scout Rifle was written with the piercing logic that was typical of his style and I gained an intellectual appreciation of the concept, but the gun was just so far removed from my O’Connor-paradigm that I couldn’t quite buy into it. It was unconventional and therefore uncomfortable. At this point in my life I was exclusively shooting sporting clays so could tread water rifle wise and continue to ignore the issue. That all came to a screeching halt when I attended my first Cooper Reunion/Theodore Roosevelt birthday event at the NRA’s Whittington Center.

At that event Il Ling New, one of Gunsite’s most popular and talented instructors conducted a Scout Rifle clinic which included a classroom session and a “rifle walk.” The rifle walk was a live-fire course comprised of metal silhouettes placed in obscure or hidden positions along an arroyo. Distances varied from about 30 to 350 yards. My good friend, Col. Clint Ancker offered to loan me his Steyr Scout and ammunition so I jumped in, skeptical, but willing to try. I apologized to Il Ling in advance for my lack of training on that weapon platform and off we went, up the target laden gully. My previous rifle training, both military and civilian had all been battle-rifle/carbine-centric. My bolt-gun experience was self-taught and revolved around copious amounts of prairie dog shooting with long, heavy barreled, target-scoped rifles, therefore the Scout Rifle was terra incognito to me. To make a long story….well, intolerable……I was amazed at how much fun that stumpy little rifle was. Il Ling’s coaching was superb. I knew enough to keep the rifle shouldered while working the action between shots and hoped that I wouldn’t poke my eye out with my thumb while working the bolt! The Steyr’s action was as smooth as buttered glass and my only failure was short-shucking the bolt once. The Ching sling was a different story however. I felt like a mule with a poorly tied diamond-hitched-pack coming untethered. I mentioned to Il Ling that I clearly needed training and her lack of disagreement spoke volumes to me.

Il Ling New, one of Gunsite's most talented and popular instructors going over proper rifle-handling protocol.

Fast forward a few years. I had acquired a used Steyr Scout but with a lack of a structured environment had fired it exactly once. The Ching sling on my rifle was as much like wrestling with a snake as it had been with Clint’s rifle and my enthusiasm had clearly faded. One day I received an email from Il Ling notifying me that the Scout class that I requested was being put together for the spring of 2019; I was on the phone with Gunsite within minutes confirming my enrollment.

When we gathered on day one of the three day class, I was happy to see that I knew all but a couple of my fellow class members. “Ravensfolk” celebrity Lindy Wisdom (Jeff Cooper’s youngest daughter) was in the class which added a sanctity of endorsement to the material that was being covered.

With Il Ling calling her hits, Lindy Wisdom (Col. Cooper's youngest daughter) utilizes shooting sticks while shooting the "African Walk" course.

Our instructors were Il Ling and Mario Marchman who are among the very few individuals still instructing who were students of Col. Cooper. They also have actually used the Scout Rifle in the field. Their anecdotal comments referencing using the Scout in Africa added an obvious element of credibility. According to Il Ling, “I taught pretty much all the ‘270’ rifle classes. Around 2010 or so, I noticed that more Scout rifles were showing up, so suggested to Gunsite management that we offer a class that would provide more Scout-centric content. Even then, Mario was one of the few ‘true’ Scout guys —in other words, he had had one for a long time, used it, knew it, etc. so he joined me on it.” The instruction, demonstrations and coaching were seamless between the two of them. Their chemistry enhanced the class significantly.

Chronologically driven descriptions of shooting classes are journalistic Sominex so I’ll spare you the agenda but attempt to hit the beneficial high-points.

The merits of the Scout Rifle “concept” are empirically confirmed not intellectually perceived and those virtues lie not in its shooting but in its handling. The Scout rifle is not more accurate than my O’Connor-inspired Model 70’s, but it carries and maneuvers far better. Therefore for me the impact of the class centered on gun handling more than it did on shooting.

A slung rifle is the equivalent of a holstered handgun and virtually every drill began with the rifle slung in one of three positions: European, African or American carry. A promotional video that Il Ling did for Ruger describes each in detail and more importantly outlines the steps to bring the rifle into a firing position. These positions and the maneuver onto target were practiced until they felt as smooth as the 5-step draw process drilled into every Gunsite handgun student.

Mario Marchman coaches a student as he uses available support on "The Scrambler" course.

At Il Ling’s suggestion, I switched from the traditional 3-point Ching sling to a Galco Safari Ching sling. The Safari version is a 2-point sling with a longitudinal split down the middle of the forward end of the strap. Connecting the two split sides is a cuff which is placed just above the elbow when being used for firing support. The placement of the cuff is adjustable thanks to a series of keyholes which run the length of both sides of the split forward strap. The cuff is held securely in place by two Chicago screws. For me the Safari Ching sling accomplished a couple of things. First, it made it much easier to carry the rifle slung over the shoulder as it did away with the third attachment point just in front of the trigger guard while simultaneously providing an ideal place to hook my thumb while walking with the rifle slung (like the thumbhole in the old Bianchi Cobra slings). Second, while unslinging the rifle from my shoulder, my support arm naturally slid into the split so getting the cuff up to my elbow was very quick, easy and almost intuitive, especially when compared to the original 3-point Ching sling.

A contingent of our class was preparing for a Scout Rifle safari to Africa and another of our students was a retired Alaskan that taught “Bear Defense” classes so I suspect that we had more hunting scenarios presented than the typical Scout class may encounter. Targets therefore were a mixture of animal targets as well as camouflaged humanoid silhouettes that are proprietary to Gunsite. Most of the “square range” shooting was spent conducting sling-to-snap-shot exercises, reloading drills and bolt-manipulation-multiple-shot drills. These were administered on humanoid silhouettes as was “The Scrambler,” a lateral “assault course” comprised of metal humanoid silhouettes located at ranges up to 200 yards positioned in the mesquite scrub. Firing positions were designated along the Scrambler and varied between tree limbs, boulders and dead-fall logs and the targets were readily visible, allowing students to maintain a brisk pace. The other field courses (the “Vlei,” “African Walk” and “American Walk”) employed metallic animal silhouettes set at distances up to 350 yards, generally hidden in shadows or behind bushes. With no designated firing positions, these exercises were a test of scanning, target acquisition and identification as much as marksmanship and gun-handling. Rarely has the “gong” of a projectile hitting a steel target been more gratifying than on these field exercises.

Col. Clint Ancker combines the stability of the sitting position with the added support of a tree stump on the "American Walk" course. Below, the superb handling dynamics of the Scout Rifle and the benefit of the long eye relief scope became apparent to the author when he engaged the robotic Buffalo.

The pinnacle exercise of the course was shooting on the robotic mover. Gunsite has employed Northern Lights Tactical robotic target systems for a number of years. During previous classes I’d experienced it with both handguns and carbines and, as the saying goes, “it’s the most fun you can have with your clothes on”……well……with a firearm. The target is remote controlled and can move as sedately as a sloth on Prozac or as frenetically as a chihuahua on a caffeine rush. The target mounted on the robotic chassis was a depiction of a quartering Cape buffalo. Since the distance was 40 yards, even at full speed, lead was not an issue with a .308, nor was scope/bore offset. The goal was to smoothly work the bolt, superimpose the cross hairs on the kill zone and not let the adrenaline dump alter your trigger press while emptying your magazine on every “pass” of the target. The target passes were generally lateral with an occasional perpendicular attack, simulating a charging Buffalo.

“Epiphany” may be a five-dollar word for a fifty-cent experience, but I had one during that robotic-target exercise. Manipulating the stumpy little rifle had always felt “comfortable” but this engagement cemented the benefits of tracking the target with both eyes open, allowed by the low-powered, long eye relief scope. The binocular vision (both eyes open) was of significant benefit when the robot would quickly change directions, a maneuver that would be much more difficult with monocular vision utilized with a traditionally mounted scope of higher power.

In the theory of right brain/left brain psychology, Cooper’s, “The Art of the Rifle,” and Richard Mann’s excellent, “The Scout Rifle Study,” can certainly convince your left brain of the logic of the Scout Rifle platform. However, until you experience them in a structured, disciplined environment such as a Gunsite class, your right brain commitment will levitate. At least mine did. In only three days with Il Ling and Mario, the Scout Rifle captured my affection, my right brain is now fully committed.

I still hold dear to my O’Connor-spawned love of old Winchesters. However, I’ve now discovered that there’s room in my heart, and gun-safe for other options.

- Greg Moats

Greg Moats was one of the original IPSC Section Coordinators appointed by Jeff Cooper shortly after its inception at the Columbia Conference. In the early 1980’s, he worked briefly for Bianchi Gunleather and wrote for American Handgunner and Guns. He served as a reserve police officer in a firearms training role and was a Marine Corps Infantry Officer in the mid-1970’s. He claims neither snake-eater nor Serpico status but is a self-proclaimed “training junkie.”