During the ongoing health disaster (or whatever this is …), I’ve been trying to catch up on reading and consumption of video content. I’m appalled at some of the misinformation out there – and that’s just in the firearms world.

One such bit of beclowning was a video in which the term “Saturday Night Special” was mentioned. Another featured a revolver drop safety mechanism, the transfer bar, described as “the thing that blocks the hammer and keeps the gun from firing.”

Sadness descended upon me. Mistake? I make mistakes routinely – and feel foolish – but there’s no need to share it. The first thing we need to dispense with is the racist terminology (yes, I said it). Then we’ll deal with positive drop safety, equally provided in DA revolvers with hammer block technology or the use of the transfer bar.

The rather stupid term Saturday night special became “popular” with prohibitionists in the 1960s, whether or not they were aware it was an offensive term. They meant “small, easily concealed handguns, especially of low quality and low cost, often used in crime (sic)” – and used by the less affluent citizens who lived in high crime areas … An article by William Tonso in a reason.com article referred to “Gun Control: White Men's Law” (his title) in which he demonstrated that “Gun control is really people control. And guess which people the power elite wants to control …”

Now for the technical aspects. A transfer bar isn’t something that “blocks the hammer and keeps the gun from firing.” That’s a hammer block safety, popularized by Smith & Wesson back in the early days of the Hand Ejector revolver series. They became aware that fully loading the gun was hazardous; dropping a loaded gun without that (and other) safety features meant the gun would likely fire if it landed on the hammer.

They handled that in a couple of ways. The rebound slide is built up matching a protrusion on the hammer. That physical contact, a ‘safety rest,’ prevents the hammer from moving forward if the gun is dropped on the hammer.

They added a hammer block, a stamped metal bit with a cross bar at the top and a stirrup at the bottom. As the trigger is pulled, the rebound slide is pressed back. This removes the projection on the slide from the path of the hammer extension. It also lets the hammer block drop, allowing the hammer access to the firing pin (in current guns) and allowing the hammer nose free travel to reach the primer (in older versions). (A great explanation of the S&W revolver drop safety aspects is provided by Larry Potterfield at MidwayUSA, found here.)

That’s not a transfer bar. A transfer bar is the opposite of the hammer block. If you remove the hammer block from a S&W revolver, the gun still fires; in fact, it could well fire when you really don’t want it to. (Check your used S&Ws; idiots routinely remove the hammer block for reasons I don’t comprehend.)

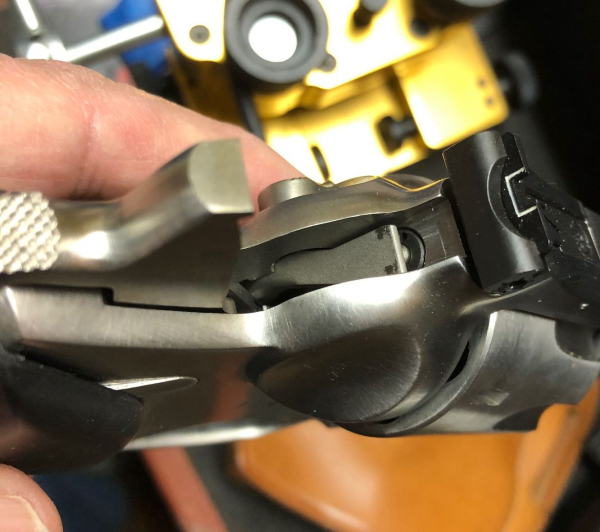

Remove a transfer bar from a revolver so equipped and it won’t fire. The transfer bar is so named because it transfers the impact of the hammer to the firing pin. If the bar is missing, the hammer won’t strike the firing pin, making the gun an expensive paperweight.

The top of the hammer on, say, a Ruger GP100 has a projection on the front that strikes the frame and prevents the hammer from reaching the firing pin. The transfer bar is moved up to cover the firing pin as the trigger is pressed, allowing the force of the falling hammer to be transferred to the firing pin … hence the term “transfer” bar.

Is it important to know the difference? Well, it’s critical to know how the firearm is supposed to work. It’s also important to know the safety features of the gun are intact and functional.

As to making mistakes, there’s a good way to admit to them – and to sort them out. The difference between hammer block and transfer bar is explained -- after a mistake -- by Hickok45, here.

-- Rich Grassi